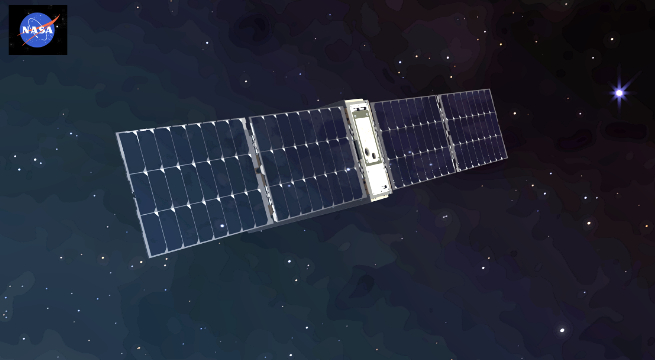

NASA’s BurstCube, a shoebox-sized satellite designed to study the universe’s most powerful explosions, is on its way to the International Space Station.

in 2023.

The spacecraft traveled aboard SpaceX’s 30th Commercial Resupply Services mission, which lifted off at 4:55 p.m. EDT on Thursday, March 21, from Launch Complex 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. After arriving at the station, BurstCube will be unpacked and later released into orbit, where it will detect, locate, and study short gamma-ray bursts – brief flashes of high-energy light.

“BurstCube may be small, but in addition to investigating these extreme events, it’s testing new technology and providing important experience for early career astronomers and aerospace engineers,” said Jeremy Perkins, BurstCube’s principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

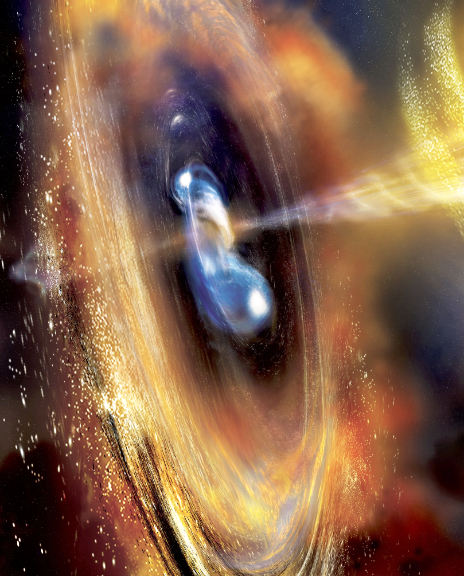

Short gamma-ray bursts usually occur after the collisions of neutron stars, the superdense remnants of massive stars that exploded in supernovae. The neutron stars can also emit gravitational waves, ripples in the fabric of space-time, as they spiral together.Astronomers are interested in studying gamma-ray bursts using both light and gravitational waves because each can teach them about different aspects of the event. This approach is part of a new way of understanding the cosmos called multimessenger astronomy.

The collisions that create short gamma-ray bursts also produce heavy elements, such as gold and iodine, an essential ingredient for life as we know it.

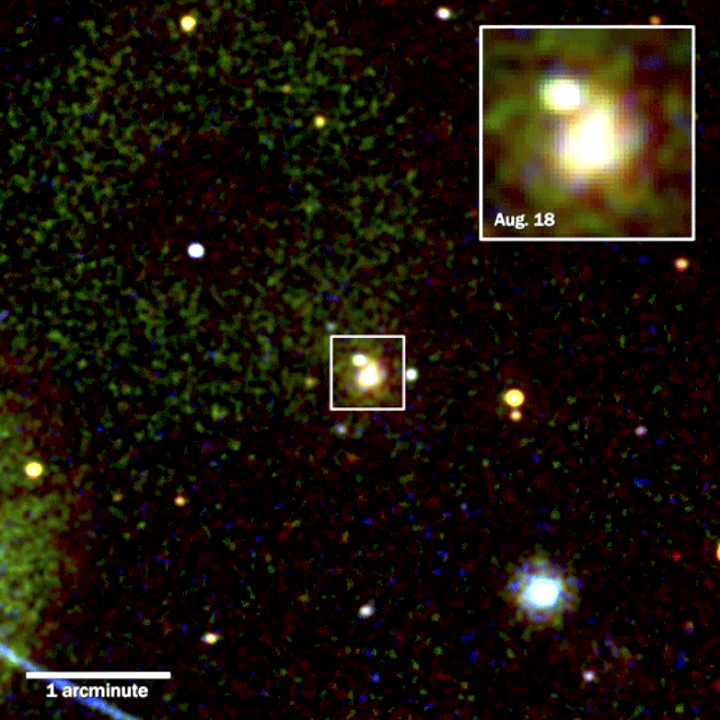

Currently, the only joint observation of gravitational waves and light from the same event – called GW170817 – was in 2017. It was a watershed moment in multimessenger astronomy, and the scientific community has been hoping and preparing for additional concurrent discoveries since.

“BurstCube’s detectors are angled to allow us to detect and localize events over a wide area of the sky,” said Israel Martinez, research scientist and BurstCube team member at the University of Maryland, College Park and Goddard. “Our current gamma-ray missions can only see about 70% of the sky at any moment because Earth blocks their view. Increasing our coverage with satellites like BurstCube improves the odds we’ll catch more bursts coincident with gravitational wave detections.”

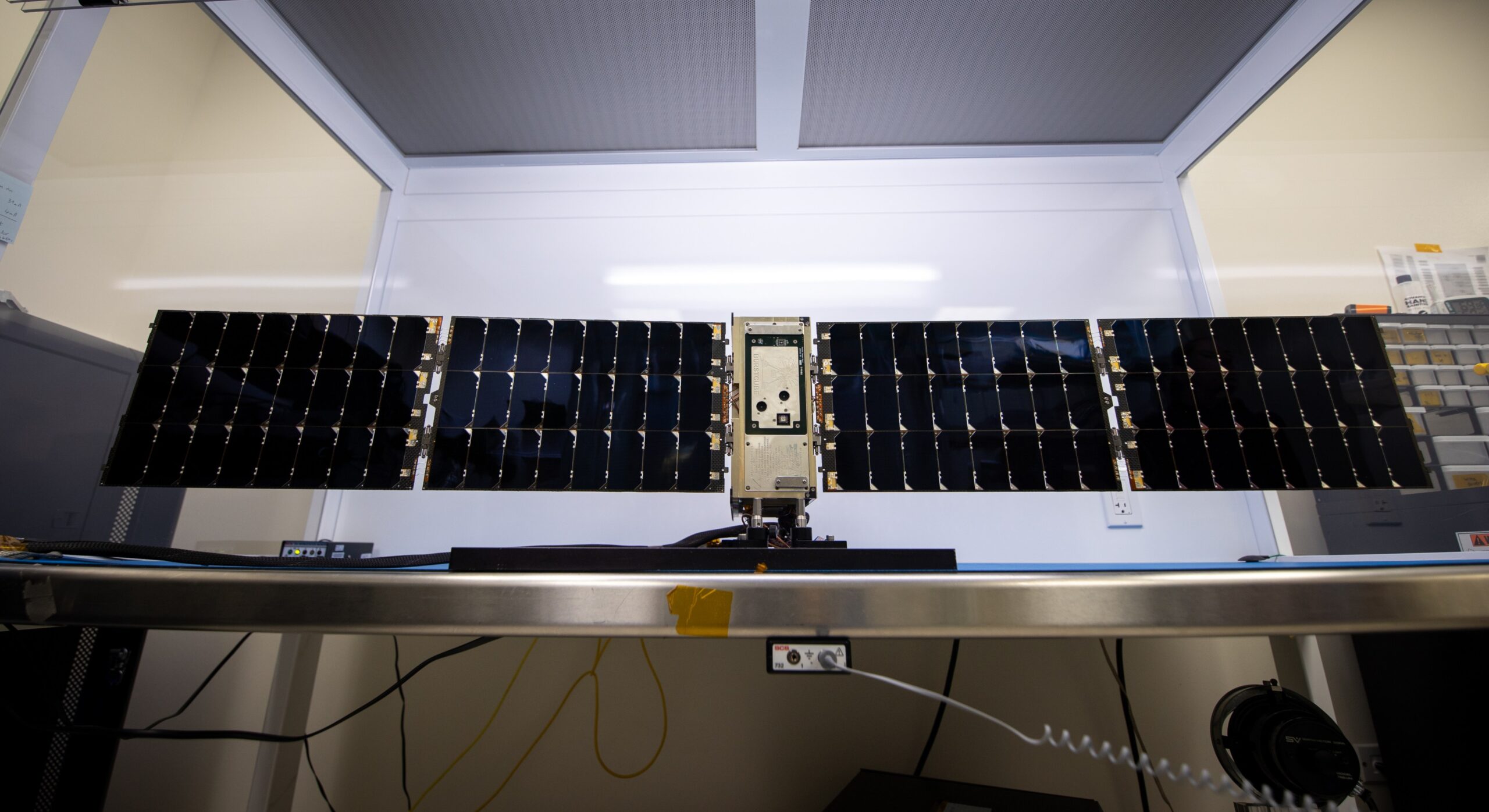

BurstCube’s main instrument detects gamma rays with energies ranging from 50,000 to 1 million electron volts. (For comparison, visible light ranges between 2 and 3 electron volts.)

When a gamma ray enters one of BurstCube’s four detectors, it encounters a cesium iodide layer called a scintillator, which converts it into visible light. The light then enters another layer, an array of 116 silicon photomultipliers, that converts it into a pulse of electrons, which is what BurstCube measures. For each gamma ray, the team sees one pulse in the instrument readout that provides the precise arrival time and energy. The angled detectors inform the team of the general direction of the event.

“We were able to order many of BurstCube’s parts, like solar panels and other off-the-shelf components, which are becoming standardized for CubeSats,” said Julie Cox, a BurstCube mechanical engineer at Goddard. “That allowed us to focus on the mission’s novel aspects, like the made-in-house components and the instrument, which will demonstrate how a new generation of miniaturized gamma-ray detectors work in space.”

BurstCube is led by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. It’s funded by the Science Mission Directorate’s Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. The BurstCube collaboration includes: the University of Alabama in Huntsville; the University of Maryland, College Park; the University of the Virgin Islands; the Universities Space Research Association in Washington; the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington; and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville.

Article is by Jeanette Kazmierczak, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland.