By Abbey White, Staff Writer, SatNews

Dispatch from SmallSat Symposium. Coverage and analysis from across the conference, tracking the forces shaping the next phase of the SmallSat market.

MOUNTAIN VIEW — If there was any doubt that the center of gravity in the commercial space sector has shifted from venture capital speculation to kinetic necessity, that doubt was shattered by the final session, Smallsats at the Tactical Edge – Hybrid ISR and Defense Integration. SmallSat Symposium this year was no longer about democratization for the sake of access. It is about survival, deterrence, and the industrialization of the kill chain.

The session’s panelists—representing the bleeding edge of propulsion, sensing, and compute—made one thing clear: Any distinction between a commercial satellite and a military asset has effectively evaporated.

The Department of War Reality

The rhetorical shift was immediate and jarring. Throughout the session, speakers abandoned the polite euphemism of defense in favor of a blunter reality.

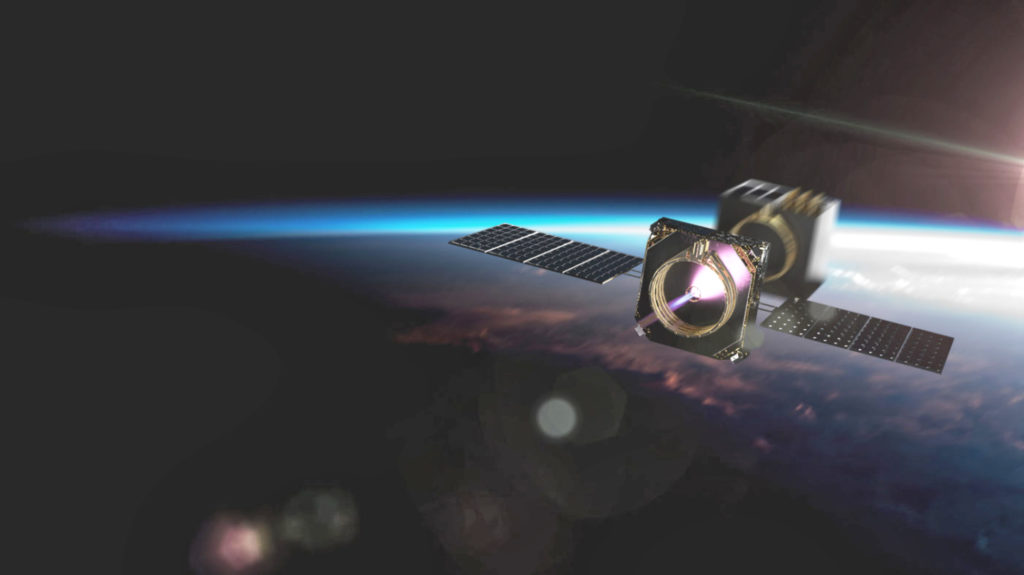

“The Department of War? Doesn’t just roll off the tongue,” Impulse Space President Eric Romo remarked, acknowledging the strange bedfellows of Silicon Valley innovation and lethal force. Yet Romo admitted that the Pentagon is where the industry’s traction lies. This is not a reluctant partnership, but a necessary fusion driven by the Space Development Agency and its spiral development cycles, which have forced a terrifying pace on an industry used to moving slow.

The mandate is integration prior to crisis. Gone are the days when commercial space acted merely as a break-glass emergency backup for bandwidth surges. Commercial sensors are now weaving inextricably into the operational fabric before the first shot is fired.

Decision Superiority, Not Just Data

The panel dismantled the legacy obsession with resolution and bandwidth. In a contested environment, a pretty picture is useless if it arrives twenty minutes late. The new currency is latency.

Mark Gombo of HawkEye 360, a former Marine electronic warfare officer, cut through the technical noise. “I submit that it’s more about decision superiority,” Gombo argued. “It is the decision space to understand what’s going on.”

This aligns perfectly with the tactical realities seen in Ukraine and Gaza, where commercial signals are jammed and logistics chains are hunted by AI-enabled sensors. The objective is no longer to hoard terabytes of data, but to deliver a target track to a weapon system.

Jonny Dyer, CEO of Muon Space, reinforced this urgency, noting that whether tracking wildfires for first responders or missile trucks for the SDA, the requirement is identical: “We really have to rethink how we architect a lot of these core systems to enable what I think is really ultimately a latency driven requirement.”

The Friction of Space Compute

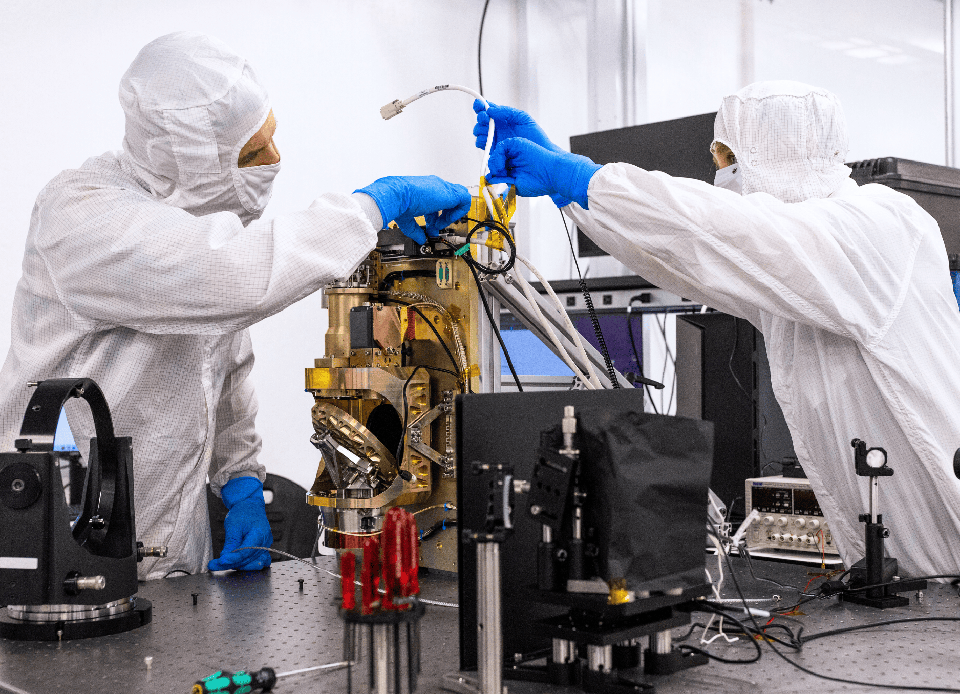

Despite the unity on mission, the panel fractured over the how. A sharp disagreement emerged regarding the role of edge computing and specifically whether to process data on the satellite or on the ground.

Jeff Janicik, CEO of Innoflight, championed the need for trusted, high-assurance on-orbit computing. To close the latency gap, he stipulated, the decision loop must move to space. “We all know that we can, if we can take the decision making and all the data collection and data fusion that is currently happening on the ground, bring it into the space,” Janicik claimed. The barrier is not the processor, he emphasized, but the trust required to let an AI make a decision that could trigger a kinetic effect.

Dyer was less convinced. In a moment of refreshing candor that typified the session, he pushed back against the industry obsession with putting data centers in orbit.

“I might be the outlier on this panel, but I just don’t think space compute’s that interesting of an idea,” Dyer said. “Ultimately, we shouldn’t care where processing is being done.”

Dyer’s skepticism highlights a critical engineering tension. Launching high-power GPUs into orbit creates massive thermal management headaches, a point reinforced by research on Andy Kwas’s work at Northrop Grumman. If the communications link is fat enough, processing on the ground is cheaper and easier. The satellites, Dyer argued, should look like a data center rack, but the software must be agnostic.

The Debris Euphemism

The most telling exchange occurred when moderator Andy Kwas raised the topic of debris removal and the recent DIU solicitation for de-orbiting unprepared satellites. In the polite society of civil space, this is an environmental discussion. In the context of a hybrid space war, it is a discussion about clearing lanes and neutralizing threats.

Romo stripped away the pretense entirely, asking the room, “Does anybody actually believe that that’s about space debris?”

The laughter was nervous but knowing. Janicik concurred, noting that right now the Department of War would be more focused on fighting through it.

The implication is heavy. Technologies developed for active debris removal are dual-use. If you can grab a dead satellite to de-orbit it, then you can grab a live adversary satellite to disable it. The industry is building ASAT capabilities under the guise of environmental stewardship, and everyone in the room knows it.

Are We Actually Ahead?

For all the bravado about American innovation, the panel ended on a note of strategic anxiety. When asked if the United States maintains superiority over peer adversaries, the answers were mixed.

Gombo was confident: “Absolutely.”

Romo, conversely, pointed to the lack of situational awareness in higher orbits, specifically Geostationary Orbit where critical national assets reside.

“I’m not so sure that—for battlefield awareness in the battlefield of GEO and probably MEO as well—that we actually are ahead,” Romo warned. He cited Chinese RPO-capable spacecraft performing inspection loops around U.S. assets with little public response.

The Bottom Line

The SmallSat Symposium has evolved. The New Space optimism of the past decade has hardened into a cold, pragmatic focus on national security. The validated gaps are lethal, the customers are wearing uniforms, and the companies that survive will not be the ones with the best PowerPoint slides. They will be the ones that can plug directly into a classified network and help a commander win a fight.

As Gombo bluntly advised the room: “If you bring me a capability that’s not on my gap list, you’re just bringing me another rock. And I don’t need any more rocks.”